Emma Parlanti, great granddaughter of Ercole Parlanti, with

Peter Pan, Kensington Gardens, London January 2024

Alessandro Parlanti was born in Rome in 1862 on 17th October. Having worked at the Nelli foundry in Rome, he set up his own business in 1890, advertising as an Artistic Foundry using the Cera Perduta Process, with Colossals & Small Castings executed in any kind of metal.

This was a period of great change in Alessandro’s life, as he had become a father for the first time in 1889 with the birth of a boy, Riccardo, followed in 1890 with the birth of twin daughters Ada and Linda, all of the children being born in Bolsena, Italy. Alessandro’s father (Antonio) and his wife (Cesira) were also born in Bolsena.

In 1891 Alessandro was living in Scotland, and appeared in the Post Office Glasgow Directory of that year as a late entry for the 1891-2 directory, where he was listed as an artistic bronze foundry at 63 Ladywell Street. It also stated his home address as 103 Stirling Road, Glasgow, where he lived as a boarder with Ferdinando Trocchi and his family. (Ferdinando was later to become the grandfather of the Scottish novelist Alexander Trocchi.) A small advert was taken out in a couple of publications, including the ‘English Mechanic and World of Science’ magazine, which stated ‘Artistic Bronze Castings Offered‘, and gave his home address at Stirling Road rather than that of the foundry. The next listed address was for Rovini and Parlanti Bronze Founders at 7 Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell, London in August 1894. By 1895 he had moved to Fulham, London, an area teeming with sculptors and painters. He purchased the lease for the Albion Works at 59, Parsons Green Lane, Fulham, along with his short term business partner Gaetano Rovini. The works comprised a house, workshop, cottage, sheds and stabling, enclosed within a narrow, irregular quadrangle. Albion works were demolished some time ago to make way for housing. An early identified Parlanti cast has the inscription ‘Rovini & Parlanti’. Rovini appears again shortly after, The Times of 7th November 1896 carrying an article on the newly formed Central School Of Arts And Crafts, mentioning those employed as teachers and stating ‘while the teachers in moulding and casting in metal work are Messrs. Rovini and Parlanti’.

Early Parlanti casting of Caesar Augustus. Stands 335mm high. Private collection.

Early Parlanti casting of Caesar Augustus. Stands 335mm high. Private collection.

Alessandro’s knowledge of last wax casting being in demand, at a time when hardly anyone in the UK had the knowledge necessary to produce successful castings, his teaching continued. Papers very kindly supplied by the John Taylor Bellfoundry Archives state how, whilst trying to generate inscriptions on some bells in 1897, finding experts in the field proved difficult, and attempts to persuade workmen from overseas foundries to assist were unsuccessful. However in April 1898 John William Taylor junior noted in his Inspection Notebook (Vol 25 p.127) on April 20th 1898 Agreed to pay Mr Parlanti the sum of £21 for teaching us how to work the ‘cire perdu’ process for ornamenting bells – £10-10-0 to be paid at once and the balance upon us being able to work the process. Taylor’s went on to successfully cast bells by the lost wax process over a period of time, the archives showing a total of 35, but as John William junior said of his father,’ he amused himself with bells moulded by the cire perdu process, this admits to much more ornamentation but is dreadfully slow and tedious’. An accurate remark indeed on the complexities of lost wax casting.

Statue of Ralph Ward Jackson in Hartlepool, one of the earliest Parlanti castings. Photo courtesy of Dawn Young

Statue of Ralph Ward Jackson in Hartlepool, one of the earliest Parlanti castings. Photo courtesy of Dawn Young

The statue of Sir Ralph Ward Jackson being lowered onto it’s pedestal in Church Street in the 1950’s. Christ Church can be seen in the background. Photograph and information kindly supplied by Hartlepool Borough Council.

Statue of Sir William Gray in Hartlepool, an early casting by Parlanti (1898) (Photograph kindly supplied by Simone Meech)

Sir William Gray in Hartlepool. Photo courtesy of Katharine Ainger Art UK

Alfred Gilbert was a regular patron of the Parlanti foundry from 1897 onwards, and diaries kept by Gilbert reveal that his dealings with Alessandro were on an almost daily basis, particularly Gilbert’s studio diary for 1899. These diaries allow us to identify many of Alessandro’s castings for Gilbert, which vary from bronzes and plasters to silver spoons and even gold medals. These castings include Gilbert’s John Hunter bust cast in 1889 by Parlanti, and also Post Equitem Atra Cura. Alessandro cast and chased this bronze (now residing in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London) in March 1899 at the same time as producing another cast which went to the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh. Richard Dorment, the art critic and historian, when writing ‘Alfred Gilbert Sculptor and Goldsmith’ in 1986, remarked Both Cat.89 (the V&A cast) and a cast of Post Equitem Sedet Atra Cura in the Royal Scottish Academy were cast and chased by Alessandro Parlanti in March 1899. Nothing suggests that Gilbert oversaw the casting or chasing, which took place in Parlanti’s foundry at Parson’s Green, and a comparison of Cat. 89 with the earlier Birmingham cast (founder unknown) reveals how important the role of the founder could be. The startling polychromed effect of the Victoria and Albert Museum version was achieved by casting the medallion in an alloy of lead, copper and gold, the latter replacing the usual zinc and tin so that after the application of certain pickling solutions ( verdigris, sulphate of copper, nitre, common salt, sulphur, water, vinegar ) a rich reddish patination was obtained. This patination was not attempted in all Parlanti’s casts ( see the bust of John Hunter for example ) but in every case where these polychromed effects are achieved Parlanti was the founder.

John Hunter Bust

John Hunter Bust

Post Equitem Sedet Atra Cura

Post Equitem Sedet Atra Cura

Six of the figures of the saints for Gilbert’s Duke of Clarence Memorial in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor were cast by Parlanti. These were identified by Cecil Gilbert when transcribing Alfred Gilbert’s 1899 diary as The Virgin, St. Michael, St. Barbara, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, Edward The Confessor, and St. Boniface. The attention to detail that Gilbert paid to these sculptures, as with many of his other pieces at the time, was noted by Ercole Parlanti. When writing in 1924 he said Our Foundry for an instance has produced works for Alfred Gilert, R.A., which have been so elaborately worked out in wax by the Sculptor ( as the Statuettes forming part of the Duke of Clarence Memorial in Windsor Castle show ) as to be practically an impossibility to reproduce from the present bronzes. Alessandro stopped casting for Gilbert in late 1899 following a fall out over unpaid foundry bills (just over eighty pounds in total); a similar situation to Gilbert’s falling out with his previous founder, George Broad. The unfolding of events is covered in great detail in Gilbert’s diary of 1899. Business must have been good at that time for Alessandro, as Gilbert’s diary reveal that he was unhappy at the time taken to receive his casts; of note is the fact that by 1899 at the latest Alessandro had had a telephone line installed at the foundry, and also Gilbert mentioning ‘Parlanti’s brother answering the telephone‘. Richard Dorment, when writing about Gilbert’s Baby Girl bronze in Alfred Gilbert Sculptor and Goldsmith, comments ‘like many of the works cast by Parlanti, the quality of this cire perdue cast is exceptional’.

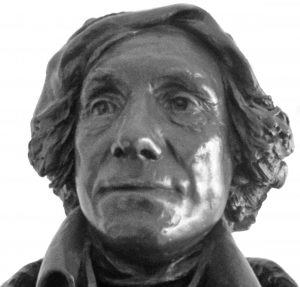

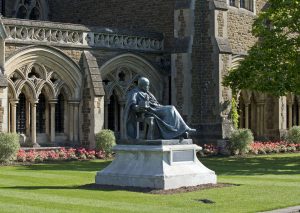

The foundry continued to produce monumental castings as well as smaller pieces. The Surrey Times of August 4th 1900 reported on a bronze statue of Dr. Haig Brown unveiled at Charterhouse School. Its execution was entrusted to Mr. Harry Bates, and this was the last work which he undertook. As, however, it was unfinished when he died, his pupil, Mr. Henry Poole, completed the task under the supervision of Mr. Onslow Ford. …The statue was cast at the Albion Works, Parsons’ Green, by Alexander Parlanti and his brother. ‘The Carthusian’ magazine of October 1900 stated: On Saturday, July 28th, the Statue of Dr. Haig Brown was unveiled by Mrs. Kendall before a large assembly. The statue which was cast by Messrs. Parlanti, was entrusted to the late Mr. Harry Bates; on his death the unfinished work was continued by his pupil, Mr. Henry Poole, under the supervision of Mr. Onslow Ford. It is placed on the south side of Chapel, near the door. The likeness to Dr. Haig Brown is striking and excellent. Among those present at the ceremony of unveiling were Dr. and Mrs. Haig Brown, and the Misses Haig Brown, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Midleton, Lord Alverstone, and the Bishop of London. Speeches were delivered after the unveiling by Dr. Kendall, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Dr. Haig Brown. The Carmen and National Anthem were sung by the choir, accompanied by the band of the Highland Light Infantry. Before the ceremony luncheon was given in Hall.

Dr. Haig Brown memorial, Charterhouse School. Image kindly supplied by Charterhouse School.

In July 1900, King Umberto I of Italy had died. Among the many tributes, came one from the Italian community of Newcastle upon Tyne, who wished to honour ‘il Buono’ by way of a bronze crown. Alessandro was commissioned to make the crown (we assume from the reports of the time he designed the crown as well as cast it). It was reported The crown, in cast bronze, is a true masterpiece: it rests on a rich velvet cushion in black silk, with a magnetic edge, and measures over a metre in diameter. The leaves and flowers are artistically worked, as well as the twigs and acorns. It is surmounted by the golden star of Italy, with an elegant ribbon underneath bearing the following inscription: Gl’ Italiani di Newcastle-on-Tyne a Umberto I il Buono, 29 luglio 1900-901. It was planned for the consular agent of Italy in Newcastle, Montaldi, to travel to the tomb of the late Umberto I at the end of July to place the bronze crown. The report further mentioned …Mr Alessandro Parlanti in London, who in just 6 years of existence with his diligence and intelligence has been able to make himself a beautiful and honored position, thus adding a new lustre to the well known Nelli foundry in Rome, from which the Roman Parlanti came out.

Bronze bust of Florence Nightingale cast by Parlanti after the original model by Sir John Robert Steell. Photo courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London. Parlanti also cast the busts of Nightingale at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London, and the Derby Art Gallery.

Although every step needed for the production of a lost wax bronze is important, the most dangerous part, and indeed the most spectacular, is undoubtedly the pouring of the molten bronze. If everything is not in order, the resulting chaos can cause injury and widespread damage including fire. In 1901 the foundry cast a large statue, that of General Gordon, which was originally sent to Khartoum. The West London Observer of Friday March 15th 1901 ran an article that gave a good insight into the casting process (and indeed a good insight to attitudes of the time). A STATUE FOR KHARTOUM.-At the Military School at Chatham there are few objects of greater or more enduring interest than the beautiful memorial to the hero Gordon of Khartoum. It will be remembered by many of our readers that the statue, which is some 14ft. in height, was designed by Mr. Onslow Ford, who chose to represent the martyr of the Soudan seated upon a camel- a characteristic attitude lending itself to most picturesque treatment. Since the reconquest of the Soudan by Kitchener, and consequent reoccupation of Khartoum, it has been resolved to place a replica of the statue in the latter city, and the work of producing the bronze cast was entrusted to Mr. A. Parlanti, of the Albion Artistic Foundry, Parson’s Green, who has been responsible for some of the most famous monuments in the Empire, his most recent productions including the Marquis of Lansdowne’s statue, the statue of Lord Roberts at Calcutta, and the Belfast memorial to Queen Victoria, which is now in hand. The most critical stage in the production of the new Gordon cast was reached on Wednesday afternoon, when the molten bronze was run into the mould in the presence of a small but influential gathering, including the artist, Mr. Onslow Ford, Liet-General the Hon. Sir Andrew Clarke, G.C.M.G., C.B., and General Sir Richard Harrison, K.C.B., the Italian Charge d’Affaires. Count F. Bottaro-Costa, Prof. S. Caneparo, and Cav. D.Regali. Before the casting took place General Harrison said a few words on behalf of Sir Andrew Clarke, expressing the hope that the work might be a complete success, and that for many years ‘’Charlie Gordon’’ might look over the deserts of the Soudan, and thus proclaim to the black men throughout that great country that Great Britain had not only conquered the land, but was endeavouring also to establish there civilisation and the fear of God. It should be mentioned that the memorial will occupy a position before the entrance to the new college in course of erection at Khartoum. Shortly afterwards the metal was released, and Sir Andrew Clarke admitted it to the mould in the orthodox manner . From all appearances the cast was completely successful, and should no mishap occur in the subsequent processes the statue will before long be on its way to the banks of the Nile.

General Gordon statue, originally at Khartoum, now at Gordon’s School, Woking

1902 saw the casting of a unique piece, the Lovat Scouts casket by the sculptor Louis Reid Deuchars.

Lovat Scouts casket

Lovat Scouts casket

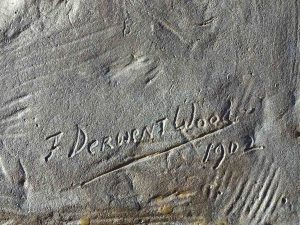

Sir Titus Salt statue, with inscriptions for Derwent Wood and Parlanti. Photographs kindly supplied by David Starley and Eddie Lawler

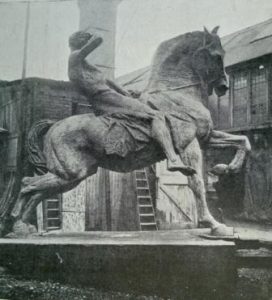

Parlanti’s castings are to found worldwide, the monumental (and original) cast of George Frederic Watts’ Physical Energy in Cape Town was carried out by Parlanti, and received substantial press coverage at the time. The Illustrated London News of 3rd October 1903 carried an article concerning Physical Energy under the heading ‘The Largest Piece Of Sculpture Ever Cast In England’, and went on to state ‘Benvenuto Cellini rediscovered the cire perdue, or ”lost wax” process of casting statues in bronze, but it was only about ten years ago that Signor Alexander Parlanti introduced the process into England, establishing the Albion Works at Parsons Green. Since then the old method of casting in sand has been discarded by our leading sculptors, and Signor Parlanti has cast most of the chief statues of our times.‘ Further press reports of the time detailed the casting, The Daily Express of October 20th 1903 stating In the little yard of Signor Parlanti at Parson’s Green the huge statue was, of course, not seen at its best. It is over fourteen feet high, and weighs almost five tons. Signor Parlanti has taken a little more than twelve months to cast it, and is very proud of his part in giving Mr. Watts’ conception to the world. The work was free from distressing incidents. It did not fall to this bronze-caster, as it did to Cellini when he cast his Perseus, to throw chairs and bed and even clothing to feed the dying fires, but he had his anxieties and dangers. It was, too, something of an experiment, for the cast of the great horse was the biggest thing of its kind that had been done in England. The group was made in three pieces- the head of the horse (which alone weighed 5-6 cwt), the rider (curiously enough, it was thought best to cast this figure separate, even to the feet), and the body of the horse. The last part was made peculiarly, because the whole front weight is thrown on one leg. This leg was cast solid up to the top of the knee-joint, and half an inch thick on the rest of the leg. The sculptor has done without the unhappy centre support which many sculptors have thought necessary to a horse in this position. A later newspaper report (The Whitby Gazette of Friday 14th October 1910), when writing about Parlanti’s castings for G F Watts stated This famous firm were responsible for the casting of the Rhodes colossal memorial statue-it weighed sixteen tons-as well as for some of the larger works of the late Mr. Watts. Further research is needed to discover which other works by Watts the article refers to.

Physical Energy in the Parlanti Yard

In G F Watts, Physical Energy, Sculpture & Site by Stephanie Brown, in chapter 5 we read of a number of reductions of Physical Energy (modelled by T H Wren following the death of Watts) produced over the years. Whilst not always possible to tell who cast them, we do know that from 1914 Parlanti certainly cast 4 reductions of a planned 50 or so, but the outbreak of war prevented any more being cast at that time. Stephanie writes It appears that after the war Parlanti carried on producing them but at some stage Wren’s name and the date disappeared. From 1928 casts inscribed with the title only are recorded and by 1938 Parlanti, having apparently lost or destroyed Wren’s original model and the moulds, began casting from surmoulage-moulds made from an existing bronze.

Alessandro’s letterheads of the time stated ‘SILVER MEDALS AWARDED-LONDON, 1897, 1904. The 1897 medal was awarded at the Victorian Era Exhibition at Earls Court in August, the 1904 medal for contributing bronzes to the Italian Exhibition, also at Earls Court. The 1904 exhibition catalogue stated that ‘Cav. A. Parlanti’ had contributed bronzes to the stand of Oswald Valli, 33 St. John’s Lane, E.C. (and Pontida) who had taken stand number 173 in Queen’s Palace, described as a ‘huge hall’. Valli exhibited artistic furniture, as well as the collective exhibit that Alessandro was part of.

Having had enough of the British climate, on 3rd August 1905 Alessandro, along with his wife and 3 children, moved back to Rome. The timing of this may also have been influenced by Ada and Linda, Alessandro’s twin girls, finishing their education at the Marist Convent, 596 Fulham Road, which they had both attended. Ercole then became sole proprietor of the Parsons Green works, the marked castings still retaining the stamp of ‘A Parlanti’, Alex Parlanti, and similar.

The foundry continued casting many pieces varying in size and metal used, two of the larger pieces were the 1906 Royal Scots Greys monument by William Birnie Rhind and also in 1906 the Boer War Memorial in Birmingham, the work of Albert Toft.

Unveiling of Royal Scots Greys 16th November 1906

Unveiling of Royal Scots Greys 16th November 1906

Toft’s work was subject to substantial renovation in 2012, and the re dedication ceremony, showing the bronze in all of its former glory, was carried out later that year with a large group in attendance, including the Lord Mayor of Birmingham. The sunny weather that day only helped to show how glorious the work was.

Birmingham Boer War Memorial, Cannon Hill Park

Birmingham Boer War Memorial, Cannon Hill Park

An example of smaller, intricate work cast by Parlanti was the Past Master Jewel cast for the Arts Lodge No. 2751, which was a Masonic lodge created by artists, most of whom were also members of the Art Workers Guild. Cast in 1906, the Jewel was for Henry Harris Brown who was a painter and one of the founders of the lodge. A payment for £1-5-0 was made to Alessandro Parlanti on 9th January 1906, and a further payment was made to Parlanti on 13th November of the same year. With Alessandro having returned to Rome by then, the payments made out to Alessandro would have been received by Ercole.

The jewel features the profile of the first Master, George Blackall Simonds, on the obverse, with the lodge name and number and a diagram representing Euclid’s 47th Proposition on the reverse. Every year the lodge would have got a new Master and new Past Master, but the jewel always featured Simonds’ profile. The Jewel measured 110mm x 57mm x 7mm including the ribbon and bar. These Past Master Jewels were produced from 1900 for a number of years. The lodge’s minute books are sometimes detailed, and sometimes vague, but the confirmation of the 1906 Jewel being cast by Parlanti opens up the possibility that the jewels for other years were also cast by Parlanti. I’m indebted to Martin Cherry, Librarian, Museum of Freemasonry in London, for the detailed information concerning the Past Master Jewels and for the images.

1906 Past Master Jewel presented to Henry Harris Brown ©Museum of Freemasonry, London 2024

Often, visitors to the foundry would include not only sculptors but also people of note including royals. The Homeward Mail of 20th August 1906 mentions ‘Princess Louise Augusta of Schleswig-Holstein, who was attended by Miss Beatrice Cameron and accompanied by Lady Gertrude Crawford, has honoured Miss Geraldine Blake by inspecting the fine equestrian statue recently executed by her at Signor Parlanti’s foundry. The statue is shortly to be sent to Ceylon to be erected as a memorial of the contingents furnished by that loyal colony in defence of the empire in South Africa. The Princess saw the first sketch for the statue about two years ago, when Miss Blake was at work upon it in Colombo’.

In The Fulham Chronicle of 5th July 1907, an article was written referring to Alessandro, but it was a common occurrence to confuse Ercole with Alessandro as the foundry had retained the name A Parlanti. Ercole had always sculpted for his own pleasure, including pieces cast in bronze for the family, we can therefore guess that the article may well apply to Ercole without having conclusive proof, although, given the bronze crown which was produced by Alessandro in 1901, it may conceivably apply to him also. It reads Mr. Alexander Parlanti, the well-known bronze founder, of Albion Works, Parson’s Green-lane, has just completed from his own design a magnificent wreath in bronze to be placed beside the wreath of Garibaldi in Stafford House at the centenary celebrations of the Italian hero’s birth on July 4th. The wreath, which is a superb specimen of Mr. Parlanti’s art, bears on its shield an Italian inscription. This signifies that the wreath has been presented by the Italians of the United Kingdom on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of the patriot. It is likely that the report meant to say that the bronze laurel wreath was to be placed under the existing marble bust of Garibaldi and memorial tablet. The inscription read In occasione del primo centenario della nascita di Giuseppe Garibaldi gli Italiani nei Regno Unito offersero. The centenary celebrations for the birth of one of the founders of the modern Italian state were a very big event, and were covered in great detail in many newspapers at the time, The Westminster Gazette of 4th July mentioning that a number of functions had been organised to celebrate the day, including a procession through some of the principal thoroughfares of the West End to Stafford House (now Lancaster House) where the bronze wreath was then placed. Winston Churchill was one of the dignitaries who attended.

Photograph from The Daily Mirror 5th July 1907

In September 1909 Ercole was listed as a Teacher of bronze casting at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, just as Alessandro had been some 12 years earlier. The actual listing states ‘F Parlanti’ but this can be assumed to be a typographical error.

The bronze statue of Edward V11, which stands on Tooting Broadway, was cast in 1911. One of the workers employed on the bronze was Charles Gaskin (later to found Art Bronze Fulham). Charles was a metal chaser at Parlanti’s, and, as told by his son Michael, would sometimes take a detour when driving home with Michael in the car so as to be able to pass the statue of Edward V11 and say to his young son ‘I helped make that‘! Louis Fritz Roselieb, who changed his name in 1916 to Louis Frederick Roslyn, sculpted the Edward VII statue at Tooting. Roslyn regularly had his work cast by Parlanti. His works identified as cast by Parlanti are on the ‘Castings’ page, but many of Roslyn’s WWI memorials are not foundry marked. One confirmed Parlanti cast is the Haslingden WWI memorial. The Maesteg WWI memorial is an exact copy of the one at Haslingden. With the Haslingden cast confirmed as by Parlanti, it is therefore very likely that the Maesteg bronze is also a Parlanti cast. Indeed, any one of the large number of WWI memorials sculpted by Roslyn may well be a Parlanti cast, research into this difficult area is ongoing.

Unveiling of the Edward VII statue at Tooting, London, on 4th November 1911. Photo kindly supplied by Neil Robson.

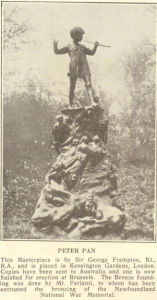

One of London’s most recognisable and loved bronze statues, Peter Pan by Sir George Frampton, which sits in Kensington Gardens (and is also shown at the top of this page), was cast by Parlanti in 1912. Conrad Parlanti, who was a young boy at the time of casting, related to a business colleague and friend some 30 years later how difficult the installation had been. In order to surprise children arriving in Kensington Gardens on May Day morning, the installation had to be undertaken overnight. The problem of getting sufficient mobile lighting to that part of Kensington Gardens had proved problematic. The quality of the modelling and of the casting is exceptional, and a visit is recommended to fully appreciate the detailing of the work.

From ‘The Veteran’ April 1924

Following the original casting of Peter Pan, a small number of copies (6) were cast. In 1935 Lady Frampton said ‘During his life my husband passed all the replicas that were made. There is one in Liverpool, America, Newfoundland, Canada, Belgium, and another already in Australia-at Perth in the West. I think that was the last one to be made and approved by my husband a few days before he died. They were all made from the cast and all went to the same bronze founder. But the cast is worn now, and the bronze founder is dead, too’. However, this cannot be correct. In 1935 Ercole was still active, albeit in a limited way, this may possibly have led to Lady Frampton thinking that the founder was dead, as opposed to semi retired. The article in ‘The Veteran’ April 1924, as shown above, states Copies have been sent to Australia, and one is now finished for erection at Brussels. The bronze founding was done by Mr Parlanti.

Peter Pan, Egmont Park, Brussels. Image kindly supplied by Quentin Demeure, Historien de ‘l’Art

Many of sculptors who used the foundry were fully appreciative of the skills that the workforce could offer, however this wasn’t always the case. Eric Gill, when writing about the finished casting that Parlanti did in 1913 of his ‘Mother and Child’ said ‘ I can see clearly enough that if I am ever to do a satisfactory bronze I must do all the chasing and finishing myself. But so far I haven’t worked on metal at all (barring tin-tacks) & so have tried to get the founders to do the finishing. I am very unhappy about it. They seem to mess the thing up first of all in the casting & then make it worse in the chasing. As soon as ever I get the chance I’m going to get hold of some tools & do some chasing myself. Everything depends on that. The bronze founders aren’t artists, they’re only mechanics.’ Despite this disparaging attitude to art bronze founders, Gill continued to have ‘Mother and Child’ cast by Parlanti between 1913 and 1917, although it is unclear as to who exactly did the chasing of the pieces, and Gill also asked Parlanti to visit Westminster Cathedral in November 1916 to take a cast in situ of the head of Christ, before Parlanti made a plaster cast from the mould with which Gill could work.

Mother and Child bronze by Eric Gill

Parlanti cast for all of the top sculptors of the period, and of particular note is the fact that he was the founder of choice for Henri Gaudier-Brzeska for the small number of bronzes and plasters cast within Gaudier-Brzeska’s lifetime. When writing his many letters to Sophie Brzeska, Gaudier mentions Parlanti quite often and simply by name, suggesting that Parlanti was well known to Sophie and Henri. On one occassion, Gaudier-Brzeska visited Jacob Epstein and remarked on one of Epstein’s bronzes. Epstein mentioned that it had been cast by Fiorini ‘whose charges are less than Parlanti‘. Despite this, Gaudier-Brzeska still chose Alessandro for his castings. Two of the four known bronze casts for Gaudier-Brzeska within Gaudier’s lifetime are known to be by Parlanti, as well as a number of posthumous casts.

1913 Casting by Parlanti. Stands 650mm high. Unusually, this bronze carries an exact date of 18-9-13 as well as the markings ‘London’ and ‘ALEX. PARLANTI’. This piece may well have been sculpted by Ercole, who was a talented sculptor as well as an art bronze founder. Private collection.

1913 Casting by Parlanti. Stands 650mm high. Unusually, this bronze carries an exact date of 18-9-13 as well as the markings ‘London’ and ‘ALEX. PARLANTI’. This piece may well have been sculpted by Ercole, who was a talented sculptor as well as an art bronze founder. Private collection.

In 1914 a reporter from the Fulham Chronicle visited the Parlanti foundry at Parsons Green Lane. His subsequent article published in the newspaper’s edition of 11th September 1914 is so comprehensive, not only in works and patrons named but particularly in terms of description of the foundry and its expansion following investment, that it is worth reproducing here in full:

Many local people have been interested in the building of the extension of the Albion Bronze Foundry, Parson’s Green Lane. Recently a reporter paid a visit and was courteously received by Mr E Parlanti and the business manager Mr G E Mercer, who not only showed him over the premises but kindly explained the processes of bronze casting. This Fulham business was founded by Mr Alexander Parlanti in 1890 and from that date the firm has steadily built a reputation amongst artists for reliable and artistic work. Entering the office, which is really a showroom, there is much to delight the eye. On the shelves are excellent models and finished work, comprising statuettes, groups, busts etc., many being by some of the leading artists of the day.

One of the latest pieces of work to be seen here is by a local artist, Mr Oliver Wheatley of Broom-house-road. This was a statuette of ‘’A Polo Player’’ in bronze. The horse, as well as its rider in the act of striking the ball, is worked out in excellent detail. *(SEE BELOW FOR DETAILS) A sketch model group of Captain Scott and his four companions, entitled ‘’Nearing the Pole’’ is to be cast in bronze. This model had just been returned from the Paris Salon summer exhibition and is the work of Mr John Cassidy, RCA. An excellent portrait bust of Queen Mary , by Sir George Frampton RA, as well as a draped memorial figure by the same artist were also to be seen.

Replying to an enquiry, Mr Mercer stated that twelve months ago with the joining into the firm of Mr J T Martin, A.M.I.C.E., the foundry was re-organised, modern equipment had been introduced, and in every way the business had been brought up to date. He also stated that by the recent extension the available space had been practically doubled. Entering this new building, which is light and lofty, attention was first attracted by a furnace which at the moment was melting bronze in a crucible for a casting. Oil fuel is used, the burner being Kermode’s patent, similar to that used on battleships. An electric motor was the medium for supplying compressed air to the flame. The system is cleaner and considerably quicker than the old coke furnaces. For larger quantities of metal there is a portable tilting furnace. Overhead is an electric travelling crane, capable of lifting five tons. This was supplied by the firm of Herbert Morris, of Loughborough, and is manipulated from the ground level in easy movements. Another interesting feature of the equipment of the foundry is an acetylene generator for oxy-acetylene welding. There is also a very serviceable pneumatic drill. Other plant includes an extensive equipment of moulding boxes which are used for sand casting, a branch of work which the firm has now developed by the extension of their premises.

For drying these sand moulds there is a special oven. After having these various processes explained and admiring a large bronze figure of Captain Cook (the work of Mr J Tweed of Chelsea) which is about to be packed and sent to the Antipodes, Mr Parlanti invited our reporter into the older part of the foundry, where the sand blast apparatus was about to be used. This is the first process for cleaning castings , for when they are taken out of the moulds there is ‘’scum’’ to be cleaned off before the work is ready to be put in the hands of the finishers. Mr Parlanti stated that the workman who usually did the sand blasting was a Fulham reservist of the 1st East Surrey Regiment, who had gone out to the front. His understudy, however, now donned the helmet , which is similar to that used by a diver, with mica window and air tube. The work being cleaned that afternoon was a memorial bas-relief to Major-General Sir Henry Jenner Scobell, and was by Mr John Tweed of Chelsea.** (See below)

The motive power for the sand blasting and the oil burners and the pneumatic tools on the premises was by a 30 horse power Westinghouse motor, which was driving an Ingersoll-Rand air compressor. The skilled craftsmen engaged at the foundry are principally Italians, but so far as possible British labour is employed. One of the workmen was giving finishing touches to a small figure, the work of Mr W Reid Dick, a large one of the same subject ,‘’Silence’’, being exhibited in this year’s Academy, and is for a tomb in Finchley Cemetery. In the old foundry workmen were preparing sections for casting of an elaborate memorial to King Edward. This is the work or Mr N A Trent, of Beaufort-street, Chelsea, and when finished will be erected at Bath.

Mr Parlanti incidentally stated that amongst the commissions they had were at least eight memorials to the late King Edward. In the foundry a portrait bust, by Mr F W Pomeroy, ARA, had just been taken out of the mould. Innumerable portrait busts have been cast by Messrs. Parlanti , these being by some of the leading British artists. In the last year or two, amongst many other important works turned out by the firm, have been a seated statue of Queen Victoria, which was unveiled at Glasgow in June by King George when on his Scottish tour. This was the work of Mr A H Hodge, of Kensington, the artist who lately won the competition for the national memorial to Captain Scott.

‘’Entente Cordial’’ was the title of a fine memorial erected near Peterborough, the artist being Mr J A Stevenson, of St. Oswald’s Studio, Fulham. This was a large eagle and is erected on a tall column. It commemorates the Napoleonic wars of a hundred years ago, and is erected at a place where a large body of French prisoners were kindly treated. ***(SEE BELOW FOR DETAILS) In connection with the King Edward Memorial at Bristol a large bronze fountain basin and groups were cast at Messrs. Parlanti, the artist being Mr Henry Poole, of Manresa-road, Chelsea. A pair of bronze lions, ten feet long, replicas of Landseer’s Trafalgar-square work, were also made at the foundry and sent out to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they have been placed at the foot of the Cabot Tower. These are but a few of the important pieces of work recently cast in Parson’s Green Lane.

Asked to describe the whole process of casting, Mr Mercer replied : ‘’The artist makes his model in clay. It is moulded and a copy in plaster is cast. This cast is the one that we are supplied with and on it we mould, either in gelatine of plaster piece-mould. From this mould we reproduce a replica model in wax. This wax is gauged to the same thickness as intended for the bronze. The hollow interior is filled with a special mixture called a core and, after attaching ‘’runners’’, the wax is covered on the outside with material, the whole forming the mould. Then the mould is placed in the kiln, subjected to heat, which not only melts out the wax but also ‘’cooks’’ the mould, passing through the ‘’runners’’ into the space left by the melted out wax.

On breaking open the mould in due time the casting is taken out and cleaned. The casting is then placed in the hands of an expert workman known as a finisher, who removes the ‘’runners’’ and stops the vents. The final stage is the colouring by chemical process to green or various shades of brown, as required by the client. Though the majority of our work is in bronze, at times we have work in silver or aluminium. ‘’ Mr Parlanti, who is a highly skilled craftsman, agreed with this brief description of the wax process. The sand process, which is suited for certain classes of work, is hardly so complicated, but produces excellent results. Asked whether the war had affected their business, Mr Mercer said that it had to a limited extent, as some of their work was held in abeyance at the moment. For the present, however, the men were working eight hours a day rather than ten. Unfortunately, some 18 months later, George Edward Mercer died after a lingering illness, aged only 43. He had joined the foundry in about 1907 as a managing clerk.

* The statuette by Oliver Wheatley was mentioned in Bailey’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes in 1914, page 301 under the heading Miscellaneous and stated ‘‘With the Ball” is the title given to a striking bronze polo statuette, a new original work by Mr. Oliver Wheatley, R.B.S., and the property of Mr. T. B Dryborough, the well-known polo player. The statuette, which is finished in brown shade bronze, shows the pony and rider in play and is very characteristic, and should appeal specially to polo men. Mr. Dryborough offers to supply replicas in bronze (10 and three quarter inches high and weighing 7 lb. 10 oz.) at twelve guineas each, which sum we understand will be forwarded as a contribution to the Prince of Wales’ National Relief Fund. Orders with remittance should be sent to Mr. O. Wheatley, Studio, 21A, Bromhouse Road, Hurlingham, London, S.W.

With The Ball by Oliver Wheatley

With The Ball by Oliver Wheatley

** The bronze plaque of Major-General Sir Henry Jenner Scobell, by John Tweed, is to be found in St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town.

Major-General Sir Henry Jenner Scobell, image kindly provided by St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town

***Interestingly, the bronze ‘Entente Cordial’ was stolen some time ago. A replacement was commissioned, and the sculptor John Doubleday was given the job. The bronze was then cast by Art Bronze in Fulham whose founder, Charles Gaskin, had worked at Parlanti’s before setting up his own foundry in 1922 in response to the huge amount of orders for bronze casting that were piling in.

Bronze lions by the sculptor Percy George Bentham at the base of the Dingle (not Cabot) Tower, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Image kindly supplied by Vistan Photography – Stephen Fralick

Nearing the pole by John Cassidy

Nearing the pole by John Cassidy

A quotation from Alessandro’s foundry to the Australian sculptor Harold Parker dated February 20th 1915 is interesting in that it gives us an idea as to the cost of casting at the time. ‘For Casting an Equestrian Statue 12 feet high from bottom of Plinth to top of man’s head, £700.0.0 13 feet high £800.0.0.‘ The quotation went on to state that the prices would vary according to the complexity of the work.

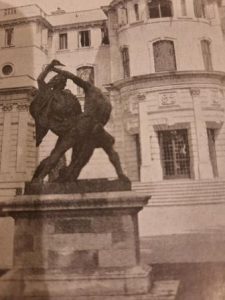

Large Group of Fighters, date of casting and sculptor unknown, cast by Parlanti. Originally at Canons Park, Edgware, present location unknown. Picture courtesy of Country Life magazine October 28th 1916

Close up view of Large Group of Fighters, originally at Canons Park, Edgware. Picture courtesy of the Friends of Canons Park

The effect of WW1 on the work at the foundry, which was evident even as early as September 1914, meant that it continued with very limited production. Papers concerning a bronze casting by Parlanti, due for completion in 1915 but not delivered until July 1916, state how the Parlanti foundry had been ordered to temporarily suspend its artistic work in order to produce vital munitions. In May 1915 Ercole had placed an advert in the local newspaper as far away as Somerset for Wanted-Moulder for Figure and High-class Ornamental Bronze. However, some castings were produced at this time. On 31st May 1916 a private view had been arranged at the foundry for a number of dignitaries to inspect the bronze cast of The South African War Memorial, destined for Brisbane. Present were Mr E J Ryan, Premier of Queensland (the Australian Prime Minister W M Hughes had been due to be the principal visitor but he had had to go to France), Mr Ryan’s wife, and James Allen, the representative of the Memorial Committee. The local press reported The little knot of workpeople and Parson’s Green inhabitants who gathered at the gates were also given the sight of further distinguished guests- A group of Australian Staff officers and a number of Australian soldiers (principally Queenslanders), who served both in South Africa and Gallipoli. Brigadier-General Sellheim, C.B., headed the military, and was accompanied by Colonel Kendal and his A.D.C., Lieut. Clarke. The energetic Mr Parlanti, having busied himself in making known everyone to everyone else, made a few remarks on the memorial, which was the object of general admiration.

An idea as to the size of the business at this time can be obtained from a local press article of November 1916, which was reporting on the case of a couple of foundry workers, John Langston (38) and Arthur George (15), both of 6 Garvan Road, Fulham, who had been charged with theft from the foundry. The article mentioned In this particular works there was £12,000 worth of metal lying about..

A letter dated 9th July 1917 to the architect Sir Robert Lorimer from the foundry concerning the Glenelg Memorial contained some notable content concerning casting of the period. ‘We endeavour to cast as light as possible with a uniform thickness of Metal to avoid unequal contraction which causes fracture and unsightly filling in with Lead, this is always objectionable & detrimental to the best Artistic work.’ The letter further states how the fine art of working out the weight and the method of casting ‘is not generally understood by ordinary founders‘. The letter was initialed on behalf of Alexander Parlanti, not signed by Ercole Parlanti, and we therefore know that by this date, at the very latest, the foundry at Parsons Green was no longer being run by Ercole, but by the new owners. When writing to Lorimer on February 4th 1918 from his Beaumont Road foundry, Ercole Parlanti mentions his previous casting work with Alessandro at Parsons Green Lane back in 1903 ‘who at that time was in London‘, and goes on to write ‘the Parsons Green works having a little time ago passed in new hands altogether’. As late as November 1918 The London Gazette reported that a licence had been granted by the Board of Trade to both James I Martin trading as Fulham Bronze Company and Alexander Parlante (sic) under the Non Ferrous Metal Industry Act. This was not an unusual occurrence, as the company name was well established.

The period following Alessandro’s return to Italy in August 1905 is proving difficult to research given the lack of paperwork or records in Italy. When writing his 1962 publication Trastevere, Capitale di Roma, Aroldo Coggiatti mentions Alessandro Parlanti, expert caster, emigrated years earlier to London, where successful castings of monuments had brought him back with several thousand pounds.

By 1919 at the very latest, Alessandro was back bronze casting in Rome. Alessandro had joined with Oreste De Lucchi & C. trading from the Trastevere district.

Alessandro Business Card

Letters in the archives at Bolsena Library show Alessandro’s dealings with the pricing, commissioning and casting of the Bolsena War Memorial from September 1919 though to May 1920. Offered a choice of design, Bolsena Town Council agreed on the model with the design of the arms of Bolsena with festoons for the price of four thousand two hundred Lire. The Council tried to change the design on a couple of occasions, including the size of the Victory statue. Alessandro took exception to this, and wrote to say that if the Council didn’t explain exactly what was going on then he would suspend work forever, notifying the Council that they would have to pay for the work already done and then find another foundry to do the work. He was working for a very small profit as he already had a model of Victory in the agreed size in his possession. Alessandro had to continue to write to ask for monies, including asking a friend of his who happened to be in Bolsena at the time, explaining that if the waxes were not cast then they risked being damaged. The money must have been forthcoming, as Alessandro continued with the casting. On 17th March 1920 Alessandro delivered the bronzes for the war memorial, with a balance of one thousand Lire still outstanding. It appears that by 26th April 1920 this outstanding amount had been settled. The World War 1 monument in Bolsena, Italy (birthplace of Alessandro’s father Antonio Parlanti), to the fallen from the village, which was unveiled in May 1920, contained the name of Alessandro’s son, Riccardo Parlanti. Riccardo had died on 14th July 1918 in a surgical ambulance following combat. Bibliolabo, Italy, states (after translation) ‘Several local workers were employed for the work of the monument, while the bronze pieces (from the bottom: the plate bearing the names of the fallen, the ornamental garland placed almost at the base of the column, the connecting band between the two parts constituting the column and the Statue of Victory) were the work of the Fonderia artistica A. Parlanti of Rome.’ Most of the bronze pieces, including the Statue of Victory, were removed for the war effort in 1940, and a different figure was later cast and put atop the Memorial. The Bolsena War Memorial was also moved from its original site in Piazza Umberto to its current location at Via Cassia Vecchia/Via Antonio Gramsci.

Bolsena War Memorial, original castings and location. Image courtesy of bibliolabo.it

Bolsena War Memorial, original castings and location. Image courtesy of bibliolabo.it

The foundry at Parsons Green Lane passed to James Martin, who went on to form two short lived companies: The Albion Art Foundry Ltd. in July 1919 and The Fulham Bronze Company Ltd. in December 1920. The new owners of the foundry continued to use the letterhead of Alessandro, no doubt to benefit from the first class reputation that had been established over the previous twenty years or so. The telephone directories continued to list Alessandro for some time after his departure. Alessandro’s brother Ercole, who had worked alongside him for so many years, started his own foundry just over a mile away at West Kensington.